Hunting Montana Sapphires

Early June saw me flying to Helena, capital city of Montana, USA to participate at the second international gemmological conference organised by my gem friend Branko Deljanin FGA. The trip consisted of three parts: the multi day conference in a Helena hotel; visits to the primary and several alluvial sources of Montana sapphires and a visit to a ‘heater’ of local mined sapphires; then recreation time spent around Montana including a visit to Yellowstone Park.

I recall soon after joining the London laboratory in the late 1970s the director, Mr Farn, pulled me away from my diamond work (my early career was devoted entirely to the quality evaluation, or grading, of polished diamonds) to show me laboratory samples of sapphires from various global localities- particularly their colours and characteristic inclusion patterns. I learnt sapphires from Montana owing to their flattened tabular crystal shape are usually fashioned as rounds, many possessing rounded crystal inclusions appearing to the uninitiated as “ bubbles” and on examination under a microscope the crystals displayed a surrounding thin film halo or decrepitation halo. The finest examples of sapphires from Montana have a steely blue hue rich in tone. I grew to love the beauty of sapphires, particularly the rarer ‘no heat’ kind. Examples of which I trade today in Hatton Garden.

Early on during my Montana trip I learnt of a dichotomy in naming sapphires from that US state. Those mined underground at the primary source in the Yogo Gulch are known as ‘Yogo sapphires’ whereas sapphires extracted from the number of secondary alluvial sources are known simply as ‘Montana sapphires’; these latter crystals usually need heat treatment to bring out attractive hues of greenish blue, blue and the occasional pink. I was determined during my trip to secure examples of both “no- heat” Yogo sapphires and heated Montana sapphires. I was to succeed in my quest.

The conference party I joined had an international flavour being made up of the organisers, jewellery valuers (appraisers in American lingo), retailers, gemmologists, gem traders and one hobbyist. I counted representatives from six countries.

Our first sapphire mine visit was to the Yogo Gulch - a gulch being a local term for a steep ravine. Within the gulch is the primary source of sapphires - a dike of volcanic rock. Less than about one to six metres wide and a length believed to be about 10 kilometers long the dike has been mined sporadically since 1896 along multiple separate segments. Our conference group assembled in the Sapphire Village near the dike to meet our guide and mining specialist George Lind of the Roncor Corporation. Soon we were driven to multiple sites along the dike travelling east to west when we found ourselves at the Yogo Creek and our chance to mine sapphires.

The eastern end of the dyke. This area was first mined by an English company up until the 1920s

Significant underground production has occurred in a small area from both sides of Yogo Creek. The American mine on the east of the creek and the Vortex mine on the opposite bank. We visited both mines.

This photograph shows the area of the American mine on the east bank of Yogo Creek. Note the cleft where the Yogo Gulch cuts through the limestone cliffs.

A conference participant gathers sapphire bearing gravel from the walls of a Yogo mine.

It was fun for the group to enter a horizontal mine tunnel, hack material from its walls into large buckets then by the Yogo Creek sieve, wash and pick out the lustrous sapphire crystals from the gravel.

On the following day the group visited secondary deposits along the Missouri river. Here sapphires are extracted from terrace gravels along a 35 km stretch on both banks of the river. At least seven individual sites, called bars, have been mined for sapphires and gold.

A view of the Missouri river and mining on a bar.

At several mines we witnessed the mechanical extraction of sapphire crystals from the gravels, involving passing the gravels through screens, trammels and sets of jigs, washing and finally hand picking of the sapphire crystals.

Loading the mined gravels.

transporting the sapphire bearing gravel to the jigs.

Jigs separate the sapphire crystals from the gravel

These methods reminded me of the basic historical methods of diamond extraction I taught in my diamond tutoring days. Many of the mines sell bags of gravel to tourists to try their luck at picking out sapphire crystals.

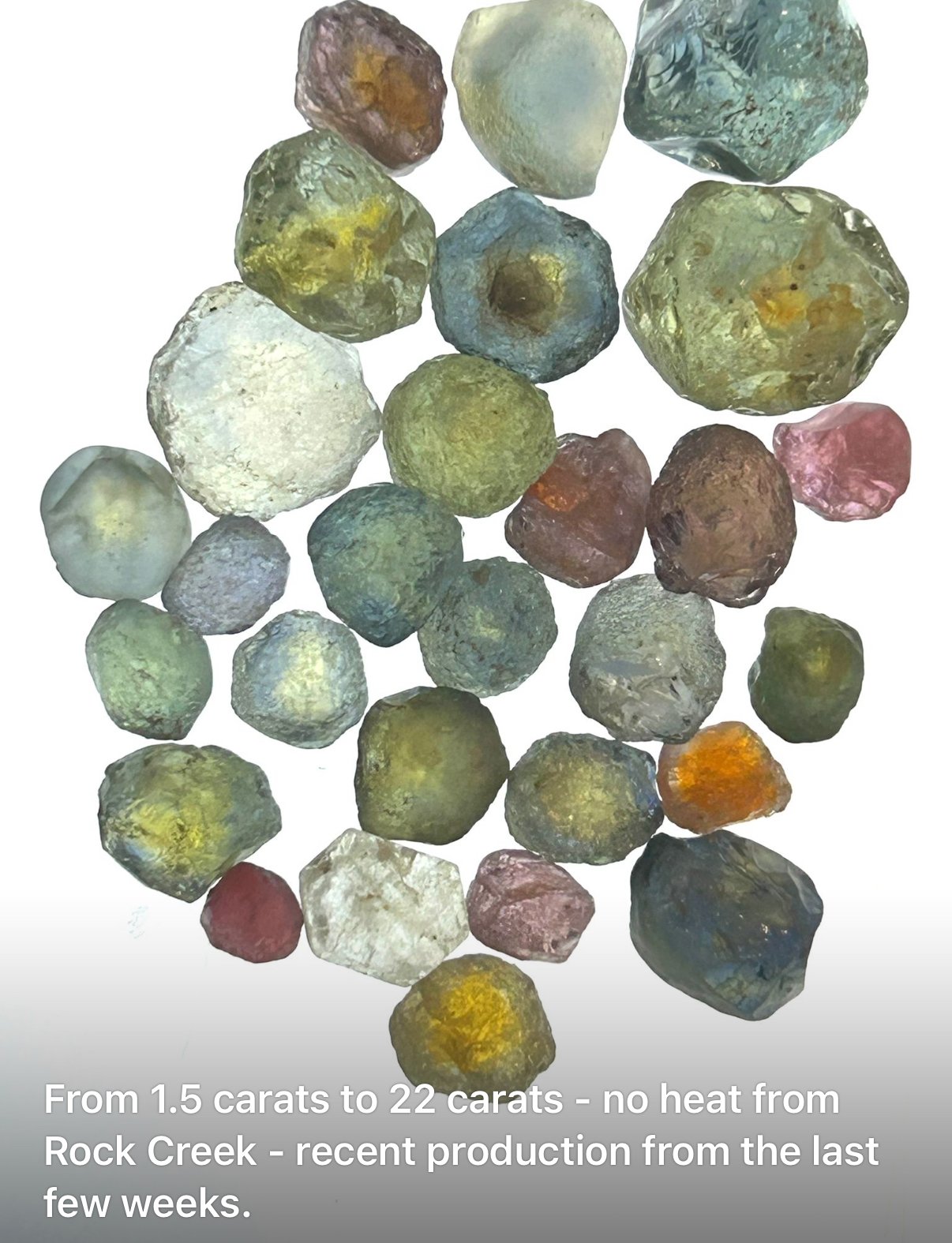

We visited another secondary source at Rock Creek near the town of Philipsburg on a subsequent day. First stop was a trip to the Rock Creek Sapphire Mine office operated by Potentate mining, where our guide Warren Boyd explained the operation and we witnessed the sieving, washing and hand picking of sapphire crystals from gravels transported from the mine.

Washing the sapphire bearing Rock Creek gravels

Warren Boyd of Potentate Mining explaining to our group how the sapphire crystals are sorted

Note the typical shapes and colour of the sapphire crystals I picked out.

At the mine at West Fork Rock Creek we saw the highly mechanised extraction methods of screening, trammelling, jigging and water extraction on a greater scale than other mines we visited. It is considered that over 1200 hectares (3000 acres) in this area,‘The Meadow’, can be exploited in the future.

Loading the mined Rock Creek gravels on to a hopper to be transported to a trommel

One of the trommels separating the sizes of the gravels

A pair of jigs separating sapphire crystals from the gravels

A view of part of the highly mechanised extraction plant.

The sapphire crystals extracted are cleaned with acids and ready for sale by tender in Bangkok. The crystals range of colours from bluish green, greenish blue and occasionally to pink and purple.

Note the colours of the sapphire crystals prior to heat treatment. Photo: Warren Boyd/Potentate Mining.

When sold, specialised heat treatment transforms the crystal colours to deeper blues, yellows and pastel hues. Heat treatment can also improve crystal transparency. I was interested to learn the primary source of these alluvial deposits is currently unknown.

We had time to visit in Philipsburg a shop selling gifts associated with locally mined sapphires and in its back room we were shown by local sapphire heating specialist Dale Siegford a kiln he uses to heat treat Montana sapphires to improve their appearance.

Crystal morphology, size, colour and inclusions

As mentioned earlier, Montana sapphires from both primary and secondary sources, are found as flattened tabular crystals, those from secondary sources show degrees of abrasion and rounded edges. When faceted most gems are cut as round brilliants and are less than one carat in weight, a two-carater gem would be extremely rare.

Yogo sapphires have a blue hue varying from faint to vivid in saturation, sometimes pink, purple and colour change stones are sometimes recovered. Alluvial crystals are mostly bluish green to greenish blue needing heat treatment to intensify the blue hue. Colour distribution throughout the crystal is even, lacking any colour banding. Crystals from both sources are of high clarity appearing clean to the unaided eye. The primary inclusions seen under microscopic examination are the decrepitation halos mentioned earlier. Noteworthy is the lack of ‘silk’ inclusions of rutile so common in sapphires from Sri Lanka, Burma and other geographical origins. These properties make for an easier decision when deciding Montana origin than with sapphires from other countries.

The gemmological conference

The conference provided an opportunity to learn and appreciate many aspects of gemmological topics. We heard from well known consultant gemmologist Lore Kiefert who has decades of experience in working for many of the most respected gemmological laboratories. Her workshop dealt with the treatment and origin determination of sapphires as well as the characteristic inclusions of sapphires from various geographical localities. For the practical element more than 50 samples from various origins and treatments were shown, most accompanied by photographs of their characteristic inclusions.

Warren Boyd, marketing director of Potentate Mining, the operator of the Rock Creek mine we later visited, outlined the extent of past and present sapphire mining in Montana, particularly the Rock Creek mine, previewing the extraction methods we saw at the site. The company is the largest producer in the state. Since its discovery in the late 1800s Rock Creek has produced over 65.8 tons of sapphire rough, approximately 90% of all sapphires from Montana.

Our group visited three of the four Montana sapphire mining sites.

The sapphire theme continued with a talk by well known consultant gemmologist Lore Kiefert who has decades of experience in working for many of the most respected gemmological laboratories. Lore spoke of the methods, instrumentations and problems of determining the geographical origin of gem quality sapphires from Kashmir, Burma, Sri Lanka, Madagascar and basaltic deposits in Thailand/Cambodia and Australia. The advanced laboratory methods to aid origin determination, such as UV-VIS spectroscopy, FTIR, EDXRF and LA-ICP-MS analysis were covered.

Another blue gem we learnt more about was turquoise. Joe Dan Lowry, whose family has been involved with the turquoise trade for years runs the Turquoise Museum in Albuquerque, New Mexico. His presentation covered how to grade quality and value various examples shown.

Joe Dan Lowry presents his talk on turquoise.

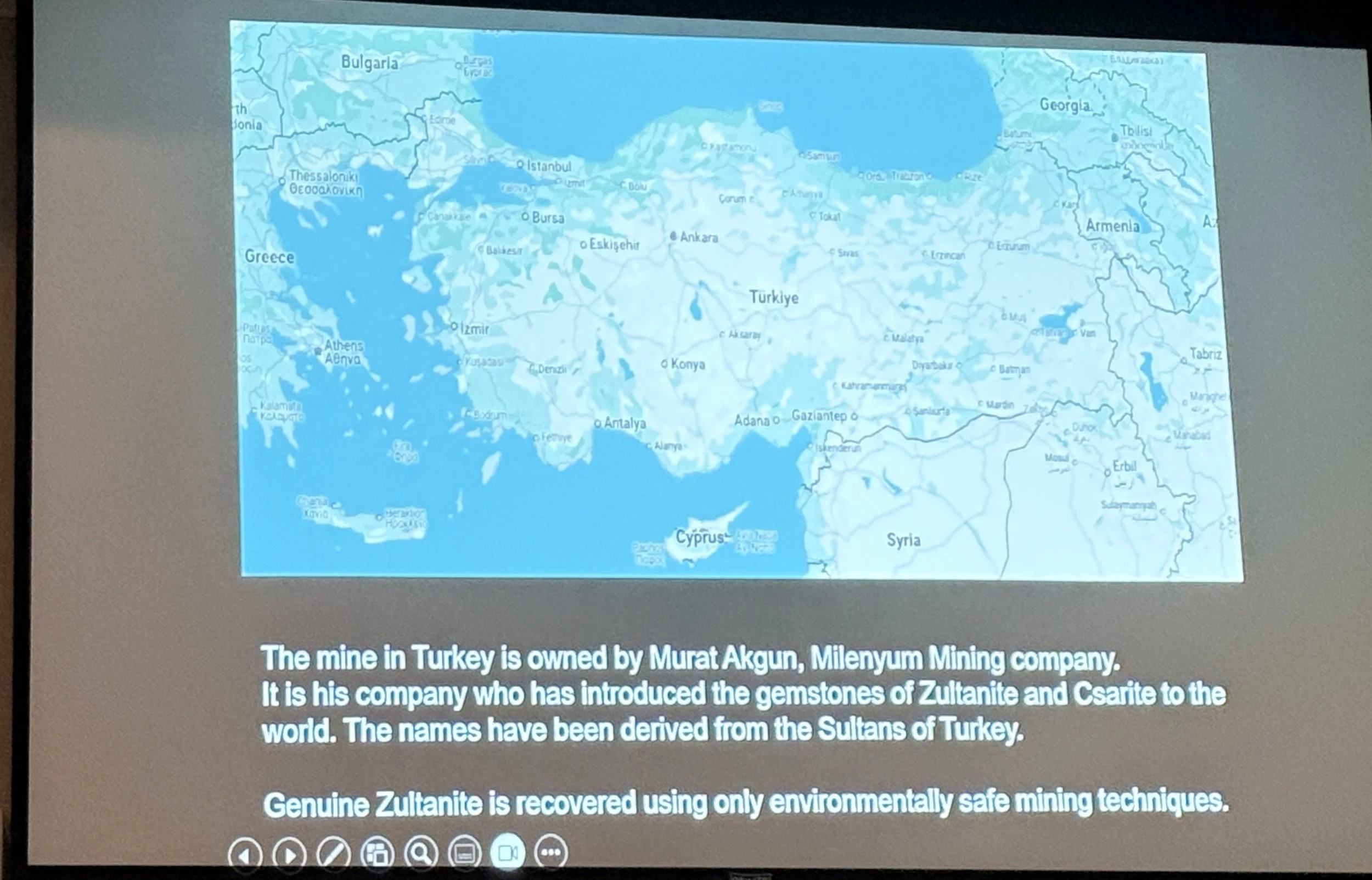

From Turquoise to Turkey where colour change diaspore is mined, Fazil Ozen, a fourth generation gem dealer, owner of Harmony Gems based in Hatton Garden and Istanbul, Turkey, spoke of Zultanite, a trade name for colour change diaspore. He informed us of its mining and marketing and showed rare examples of a cat’s-eye and bi-colour gems. Renowned for its colour change from green to pink under different lighting conditions, Fazil demonstrated the beauty of the gem and the ethical and environmental considerations of its mining.

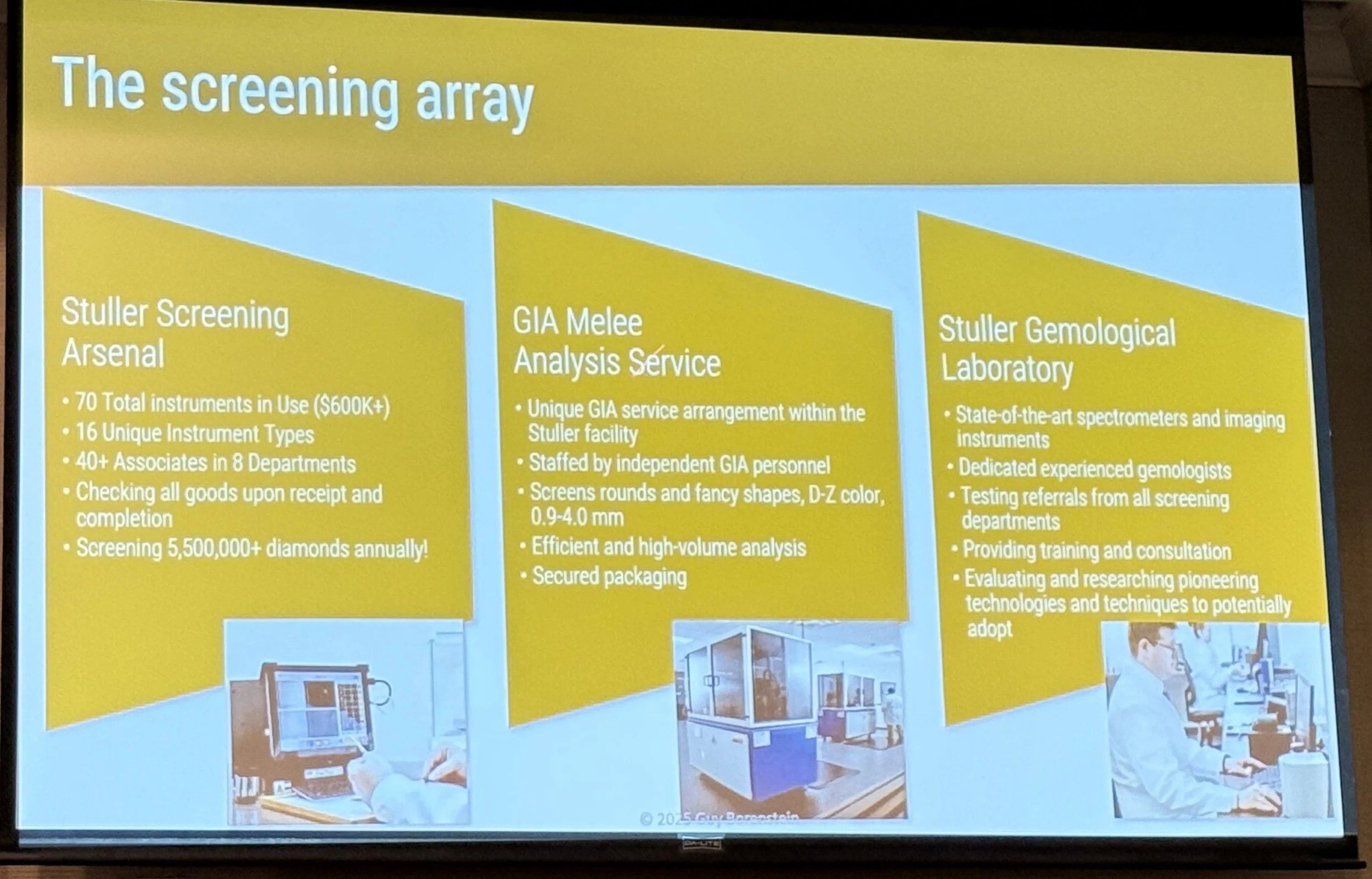

Following the lunch break, a presentation on the current availability of instruments for screening laboratory-grown diamonds (i.e. synthetic stones) was offered by Guy Borenstein, director of gemstone procurement and senior gemmologist at the US jewellery company Stuller Inc. His presentation covered each instrument's limitations as determined by Stuller’s screening tests investigations.

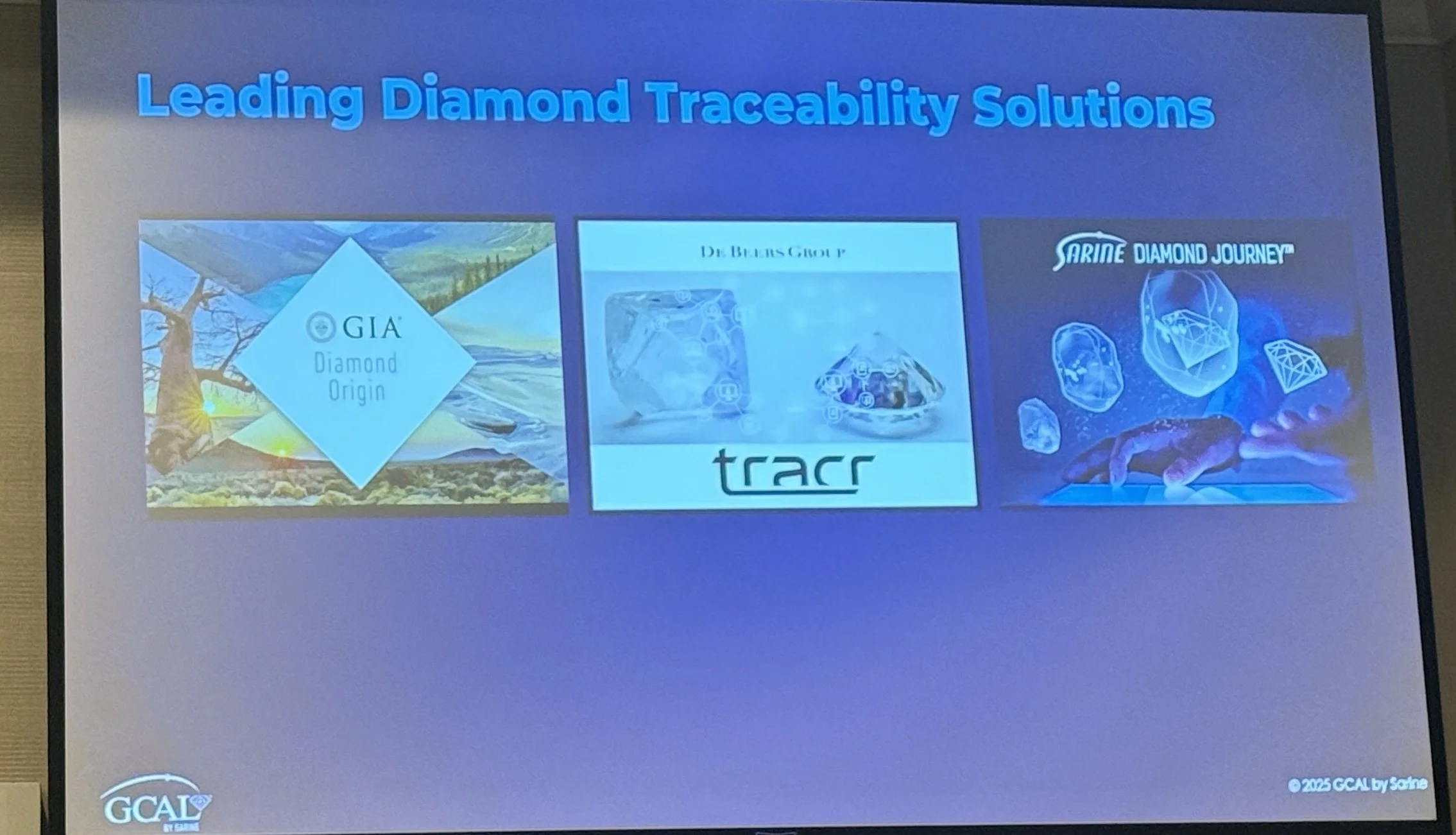

The diamond theme continued with Sharrie Woodring, senior gemologist at GCAL by Sarine gem laboratory, speaking of recent development on diamond traceability, market dynamics and diamond grading using artificial intelligence.

Traceability is gaining widespread attention owing to current U.S trade sanctions and increasing interest from retailers wishing to strengthen the narrative of natural diamonds through transparent sourcing.

The conference organiser, Branko Deljanin, informed us about the production, treatments and cutting of CVD grown synthetic diamonds in India. Based on a recent visit to Surat and its CVD grown diamond factories Branko described how the country has emerged as a leading producer of CVD grown synthetic diamonds and is home to numerous processing and cutting centres for both synthetic and natural diamonds.

We returned to Montana sapphires when Cynthia Shaver, a gem and jewellery valuer, emphasised the factors affecting the accurate appraisal of Yogo and Montana sapphires.They are valued for their US origin and historical importance. Market dynamics and trends, particularly those driven by demand for responsibly sourced and untreated gems have positively affected the pricing of sapphires from Montana in recent years.

The first day of the comprehensive conference ended with a couple ‘round table’ discussions on ‘Sapphire and Turquoise Origins’ and ‘Lab Grown vs Natural Diamonds”

The following day was given over to workshops where we had the opportunity of handling turquoise samples and its imitations,to learn how to grade turquoise quality and determine value using Joe Dan Lowry’s turquoise grading system.

Later we learnt during Branko’s workshop how to identify HPHT-grown synthetic diamonds using portable instruments and how to recognise the appearance of CVD-grown synthetic diamond when viewed using cross-polarised filters and ultra-violet lamps and how to identify some ‘overlapping’ type IIa natural and CVD-grown synthetic diamonds that need further testing. The workshop gave an opportunity for us to use the DOVE instrument by Gemetrix and the REVEAL instrument by JTR, both based on using deep short-wave and EXA by Magilabs using PL (365nm) spectroscopy.

Branko Deljanin assists Diane Chesler, a jewellery valuer, and Briana Daugherty, a jewellery retailer, both based in California, in his synthetic diamond workshop.

The knowledge I gained from my time in Montana was extensive, not only from the mine owners and workers, and a local gem specialist on the local sapphires during our field trips to the various mines but also on varied gemmological topics from the speakers at the conference.

Production volumes are tiny compared with the many current global sources notably from Madagascar and Sri Lanka yet sapphires from Montana are an enduring example of an American precious stone which I believe deserve greater recognition for their beauty by the global gem trade.

The next International Gemmological Conference is planned for 25 - 27 March 2026, to be held in Dubai and Bahrain. More details from https://www.gemconference.com/contact

Photographs by author unless otherwise indicated.

A condensed and edited note of this blog appears in the latest Journal of Gemmology (Vol 9, No. 7) 2025.